Adidas thought three was a magic number; they were in ‘four’ a shock

Thom Browne and Adidas: two global names in the fashion world who are rarely mentioned in the same conversations, unless you are in the world of IP.

On hearing ‘Adidas’, it is likely that your mind may jump to ‘the brand with the three stripes’. Adidas believe this to be the case to such an extent that it started using this as a strapline on a variety of its products.

The question is: is Adidas the only brand with stripes? Thom Browne think not, and these two entities have been arguing over the exclusivity of stripes in the fashion industry for almost two decades now.

Focusing on the most recent ruling in this long-standing saga, we'll delve into what sets valid and invalid marks apart, as well as the history of this now global dispute.

A brief history

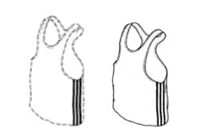

2007: Adidas contacts Thom Browne following its use of a horizontal three stripes design which it felt was too similar to its infamous vertical three stripes motif. As a result of this, Thom Browne co-operated with the sportswear giant and changed its design from three horizontal stripes to four horizontal stripes.

Thom Browne four stripes design.

At the time, this is sufficient for Adidas, and the two entities agree to co-exist with Adidas continuing to use its infamous three vertical stripes, and Thom Browne using four horizontal stripes as shown (right).

2018: After over a decade of co-existence, but also importantly a period of rapid growth for Thom Browne, Adidas reach out once more, this time requesting that Thom Browne ceases use of its stripe design entirely. At this point, Thom Browne has begun to expand into more luxury activewear, goods which overlap more directly with Adidas’ core goods, rather than its primary luxury apparel.

2021: Adidas file oppositions against trade mark applications filed by Thom Browne in the US, as well as suing for trade mark infringement, dilution, unfair competition and unfair business practices in New York. All of these claims are unsuccessful.

* Thom Browne file revocation actions against Adidas’ three stripe trade marks in the UK, on the basis of the marks being non-specific and vague, creating uncertainty as to how far the rights stretch.

2023: Adidas file similar claims against Thom Browne in Germany and is unsuccessful once more. The courts find that the differences between the Adidas’ and Thom Browne’s stripe designs are sufficient to prevent consumer confusion, paying particular attention to the difference in consumers (sportswear consumers vs luxury apparel consumers).

2024: Thom Browne Inc & Anor v Adidas AG & Ors [2024] EWHC 2990 (Ch). UK High Court hears Thom Browne’s revocation actions and Adidas’ counter claims alleging that Thom Browne’s use of its four stripe design constituted as infringement of Adidas’ three stripe trade marks.

UK High Court Ruling

Adidas has (or had) numerous registered trade marks in the UK for a variety of three-stripe designs, some of which Thom Browne filed revocation actions against in 2021.

The outcome of these revocations hosts important lessons for those in the fashion industry looking to register and maintain protection for rights which may not hold the highest level of distinctive character (such as geometric shapes).

Revocation of Adidas’ trade marks

In the UK, a trade mark must be clear and precise as to what exactly is being protected. An entity cannot have exclusive rights over a vaguely represented mark, as this opens the door to over-reaching when it comes to enforcing the trade mark.

Thom Browne brought revocation actions against a variety of trade marks held by Adidas, many of which were successful due to the Judge deeming that the registration’s descriptions were too broad and therefore likely to create confusion as to what subject matter the registrations were actually protecting amongst the public and competitors alike.

Although eight (of the sixteen challenged) withstood the Judge’s examination, the remaining eight were declared invalid, striking a blow to Adidas’ portfolio and decade old strategy of maintaining registrations for broad rights.

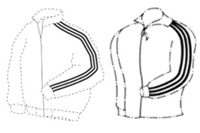

As a result of this ruling, Adidas’ trade marks bearing the following representations (left examples) were deemed to be invalid.

On the flipside, registrations with these representations (right examples) withstood the Judge’s examinations.

What’s the difference?

It is easy to focus on the graphic representations of marks such as those above, but this case proves that the description which accompanies these types of marks plays a huge role.

When comparing the graphic representations of the marks which were deemed valid and invalid, it is difficult to spot any substantive differences. This is because the Judge’s rulings focused greatly on the trade marks’ accompanying descriptions.

Tracksuit top – invalid case study

Description: “The mark consists of three parallel equally spaced stripes applied to an upper garment as illustrated below, the stripes running along one third or more of the sleeve of the garment”

Judge’s analysis

- “A member of the public, including an economic operator, looking at the register would be left in a position of uncertainty as to what the protected sign actually is.”

- “Adidas chose the words it used for this Mark and could have chosen to employ a great deal more precision or alternatively to apply to register different Marks encompassing illustrations of how each Mark was to appear on particular garments. It did neither of these things.”

The Judge explicitly rules that the graphic representation is ambiguous, but so is the description, and gives no merit to the inclusion of “as illustrated below” in assigning more specificity to the subject of what Adidas actually seek to protect.

Cap – valid case study

Description: “The mark comprises three stripes applied on a cap visor, as shown in the illustration, the shape of the cap as such does not form part of the mark”

Judge’s analysis

- “On its true interpretation, this Mark is designed to protect the Three Stripe sign as it is affixed to caps in the position shown in the illustration. Thus there is no issue as to whether the Mark must be centred on the visor, whether it is to be parallel to the visor and the amount of visor it can cover. That is all clearly illustrated by the pictorial representation and this would be understood by the relevant public.”

- “The words “applied on a cap visor” might in isolation create uncertainty and/or contemplate a variety of different forms, but when those words are seen in context with the illustration, there can be no uncertainty. The illustration is clear that the Three Stripes are to be applied vertically in the middle of the cap visor. Their width, spacing and length is clear.”

The Judge’s analysis in this decision clarifies the importance of there being a concrete relationship between the graphic representation and the description.

This example also clarifies that specific statements such as “on a cap visor” and “the shape of the cap does not form part of the mark” will assist in avoiding an invalidation on the grounds of vague representation, as long as it is in line with the graphic representation.

Adidas’ infringement counter claim

Adidas’ infringement counterclaim against Thom Browne ultimately failed. The court found that Thom Browne’s four-stripe designs were not confusingly similar to Adidas’ three-stripe marks, despite acknowledging Adidas’ widespread reputation.

The Judge focused on differences such as Thom Browne’s design being positioned horizontally, the inclusion of the extra stripe and the stripes being thicker, before concluding that there is no likelihood of confusion.

Additionally, the Judge commented on Adidas’ lack of compelling evidence to establish that the public would make a link between Adidas’ registered marks and Thom Browne’s four stripe design. Adidas’ evidence included a ‘handful’ of screenshots of Instagram comments, which the Judge noted as being cryptic before concluding that there was no credible evidence of members of the public being deceived.

Lessons learned

Filing strategy

The plethora of revocation actions discussed in this case offers a clear lesson: broad marks, on the lower end of distinctiveness (such as stripes, shapes or other geometric motifs) need to be handled strategically.

For fashion brands, this means rethinking how to register and enforce these kinds of marks. Vague or overly broad representations will need carefully populated descriptions that must strike a balance between:

- Limiting the right appropriately, so to not fall foul of the requirements; and

- Still ensuring a sufficient level of protection for future potential enforcement purposes.

Additionally, brands should get creative with the ways in which they protect their intellectual property. Whilst this case was entirely trade mark centred, Adidas may have had a better position if it had registered design rights filed to rely on.

Evidence

A lesson which brands can take away from the infringement ruling in this case is to always file extensive and conclusive evidence. Filing Instagram comments alone would never be advisable, but in this case even many of these comments were disregarded as there was no evidence that the commenters were UK based.

Commercial approach

As well as looking at what this case can teach us from a purely legal perspective, this case is an example of overly aggressive enforcement backfiring. Adidas’ persistent attempts to restrict Thom Browne’s use of simple stripe patterns not only failed, but also resulted in the invalidation of several of its own UK trade marks.

By pursuing enforcement and overreaching in litigation, brand owners run the risk of provoking counter claims which can put them in a worse position than when they started.

It is for these reasons that brands need not only legal advice when it comes to their IP portfolio, but also commercially mined and strategic advice as to when and how to take action. If you are looking for commercially driven IP advice, be sure to get in touch with the authors of this article.