Bath time drama

The Intellectual Property Act 2014 removed “aspects” from the definition of a UK unregistered design right. Cue confusion.

The IPEC decision in Shnuggle v Munchkin provides much-needed clarity on the difference between “parts” and “aspects”.

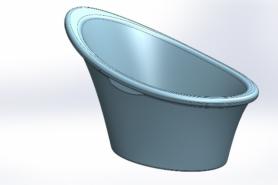

Shnuggle is a small company based in Northern Ireland that designs, manufactures and sells baby products. In 2012, Shnuggle began to design and develop its first baby bath, referred to as the Shnuggle Mk1. This was later replaced by the Shnuggle Mk2, which had the same basic outline as the Mk1, but also added features such as a backrest and an island-style bump in the base.

Put on sale in 2015, the Shnuggle Mk2 achieved significant commercial success and won a number of design-focused industry awards.

Munchkin Inc. is a large company based in the US that also designs baby products. In October and November 2017, Munchkin designed its own baby bath, first sold in January 2019 under the name “Sit & Soak”.

Shnuggle commenced a claim against the Munchkin product based on two Registered Community Designs (RCD-196, RCD-763) and six UK unregistered design rights (one in the Mk1, and the remainder in the Mk2).

Why is this case important? Primarily for its analysis of unregistered designs, the question of the day being: what constitutes “part of an article” as opposed to an “aspect”? This question arises following an amendment to Section 213(2) Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 (CPDA) by Section 1(1) of the Intellectual Property Act 2014 (IPA 2014).

Design Disputes

Section 1(1) of the IPA 2014 removed three words – “of any aspect” – from Section 213(2) of the CDPA, which previously read:

"In this Part, “design” means the design of any aspect of the shape or configuration (whether internal or external) of the whole or part of an article".

Each of Shnuggle’s pleaded unregistered designs was claimed to be a part of an article.

Munchkin submitted that the pleaded designs constituted an “aspect of the shape or configuration” and were therefore not protectable following the amendment.

Munchkin further submitted that the purpose of the amendment was to prevent claimants from excluding all those elements that are different while retaining those elements that are the same, in order to maximise the chance of an infringement finding.

In her decision, HHJ Clarke did not accept this submission on the basis that “it is specifically provided in Section 213(2) that the right can subsist in relation to the shape or configuration of the whole or part of an article”. What’s more, it is well established in case law that claimants can “trim” their design accordingly.

The distinction between part and aspects

So, does an element have to be created separately to be a “part”?

The Defendants submitted that the “part” should be created separately from the rest. So if the spout of a teapot is created separately, it can rightly be called a part, but if the teapot is made of a single piece the spout should be an “aspect”.

This submission was discerned from Neptune (Europe) Limited v DeVol Kitchens Limited, where the late Henry Carr J considered that “aspects of design include disembodied features which are merely recognisable or discernible, whereas parts of a design are concrete parts, which can be identified as such”.

With regards to “merely recognisable and discernible”, HHJ Clarke stated that:

"Of course, requiring an aspect merely to be “discernible” or “recognisable” is a very low threshold which is hardly a threshold at all. If something is neither discernible nor recognisable, it is difficult to see how one could even characterise it as a design, let alone how one could copy an indiscernible or unrecognisable aspect, or establish it has been copied. As Jacob LJ himself accepted in Fulton v Totes [at 23], a design right “is limited to preventing copying, and copyists must know what they are copying”.

HHJ Clarke concluded that a part did not have to be created separately. There is nothing in the statute which suggests separate creation is required and nothing in the pre-amendment authorities to suggest it either.

She added that “it would lead to absurdities if an identifiable part of one article (say, a handle on the lid of a teapot) was a ‘part’ for the purposes of Section 213(2) because it had been created separately… and the same identifiable part of an otherwise identical article was not, because it was manufactured in one piece”.

Pleaded designs accepted

All of Shnuggle’s pleaded designs were accepted as drafted. It did not matter that an arbitrary line was drawn, with the design being defined as everything below that line, as this was still a “part”. Indeed, the Claimant even brought the parts to Court in the form pleaded.

In conclusion on this issue, HHJ Clarke stated the position to be as follows:

"It seems to me that now the words “any aspect of” have been excised from Section 213(2), there is no longer any practical utility to considering the question: what is the difference between a “part” and an “aspect” of an article? The relevant question should now be only: is this a design for “part” of an article?

We have paragraph 10 of the Explanatory Notes to the IPA 2014, which tells us that the changes to Section 213(2) were intended to narrow the definition by excluding trivial features from protection.

Accordingly, I consider that a part of an article for Section 213(2) is an actual, but not abstract, part which can be identified as such and which is not a trivial feature. Whether or not it is a trivial feature is a matter of fact which will need to be assessed in the context of the article as a whole".

The decision was that one of the designs had been indirectly copied but that the similarities to the other designs were a coincidence.

On the design found to have been copied, due to the Judge’s interpretation of the pleaded design, the Sit & Soak was not found to be exactly or substantially made to the design.

The High Court’s decision

On the registered design claim, Munchkin challenged the validity of Shnuggle’s later design for the Mk2 (RCD-763) on the basis that the design corpus included the earlier registered design (which was also relied upon) for the Mk1 (RCD-196). As such, the later design did not have individual character.

Munchkin had dropped its case of invalidity of RCD-196 prior to trial, so there was no question of subsistence. The Judge found that Shnuggle’s later registration was invalid over the earlier one, but that the earlier one, while broad, was not so broad as to catch the Munchkin product.

Although not determinative, HHJ Clarke also considered the impact of colour and contrast on the scope of protection, as RCD-196 was found to have been registered in a shade of light blue. Noting that this may not have been the intention of the designer when he filed his registered design, HHJ Clarke held that:

In summary, it is up to the applicant for a registered design right to decide what to apply for, what features to include in the design application and what to leave out and how to represent them. As Munchkin submits, and as I accept, per Magmatic on appeal, where a design is registered in colour and/or contrast, then that must be taken into account when considering infringement, and the use of the colour and/or contrast will serve to limit the scope of the registered design.

Key points:

- A part of an article does not have to be separately identifiable or separately manufactured, provided it is not trivial

- “Aspect” is likely to relate to disembodied features that, if claimed together, would not form a single object – such as the spout and handle of a teapot, without the pot itself

- It does not matter if the claimant claims everything that falls on one side or the other of an arbitrary line

John Coldham is a Partner at Gowling WLG

Zoe Pearman, Associate at Gowling WLG, co-authored

Read more case comments

Family matters

Protecting your own must be a priority, finds Sam Barker. [2025] EWHC 3077 (IPEC), easyGroup Ltd v Jaybank Leisure Ltd.

A golden opportunity

Guidance on interpretation of figurative marks with written descriptions is welcome, writes Daniel Ramos. [2025] EWCA Civ 1341, Babek International Ltd v Iceland Foods Ltd.

The hunt for reputation

Rebecca Field reports on Puma’s appeal against a decision it said would affect its reputation. T-491/24, Puma SE v EUIPO, General Court.

Less can mean more

Brevity is a powerful tool in registering marks, finds Henry Schlaefli. [2025] EWCA Civ 1340, Thom Browne Inc & Anor v Adidas AG.

Was boiling point reached?

Despite a legitimate secondary market for its goods, AGA resisted a reseller’s exhaustion defence, writes Charlotte Lavery. [2025] EWCA Civ 1622, AGA Rangemaster Group Ltd v UK Innovations Group Ltd & Anor.

The battle of rights

The right to freedom of expression can be used to establish due cause, writes Abdulmalik Lawal. C-298/23, Inter IKEA Systems BV v Algemeen Vlaams Belang VZW and others, CJEU.