Marked for defeat

This decision was as easy as ABC, says David Yeomans.

T 399/20, Cole Haan LLC v EUIPO, General Court, 14th July 2021

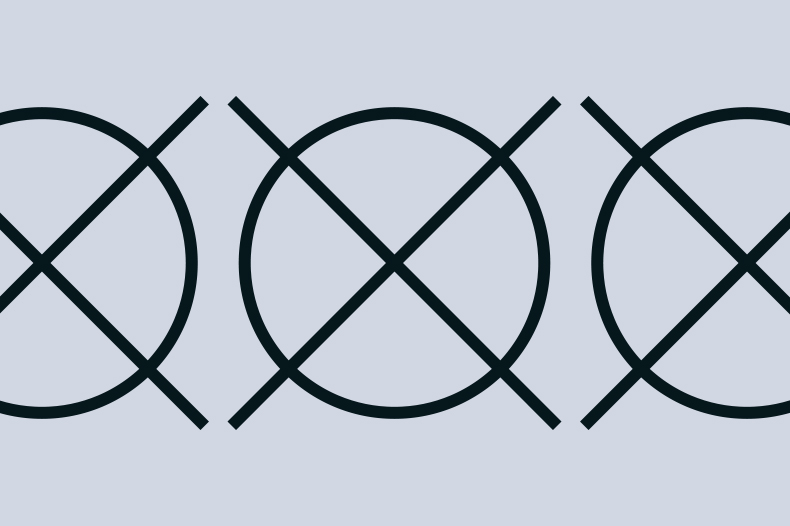

This judgment relates to two figurative marks. The Applicant, Cole Haan LLC, had applied for the Contested Mark at the EUIPO. That application was opposed by Samsøe & Samsøe Holding A/S, based, inter alia, on the Earlier Mark.

The Opposition Division upheld the opposition on the basis of likelihood of confusion. The Fourth Board of Appeal (BoA) upheld that decision on appeal. It was that decision that the Applicant then appealed.

Agreed facts

For the purposes of the appeal, the parties agreed that the BoA had been correct in determining that:

- The goods at issue were identical or similar;

- The Contested Mark is a representation of the letter Ø, which is part of the alphabet used in Danish, whereas the Earlier Mark is a representation of either the Greek letter ϕ or the letter Ф from the Cyrillic alphabet, used in, inter alia, Bulgarian;

- The relevant public was “the French-speaking public with no command of Danish, Bulgarian or Greek”.

The second and third points are each worthy of their own article. Each finding had a significant bearing on the outcome of this decision. However, being agreed, there was no real commentary from the Court on either.

The Applicant pursued its appeal, therefore, on what the Court described as “in essence, a single plea in law” – namely that there was no likelihood of confusion.

Visual comparison

In respect of the visual assessment of the marks, the Applicant argued that the BoA erred in finding that “the signs at issue both consist of a circle bisected by a straight vertical line”. The Court agreed that the BoA had erred (the Contested Mark’s line is not vertical), but found this “erroneous statement” had no bearing on the decision.

The Court stated that, elsewhere in its decision, the BoA had referred to both the vertical and horizontal line, and properly reproduced both marks, making clear that it had properly considered the visual differences.

The Applicant further argued that “the relevant public is accustomed to distinguishing letters with similarities”. The Court, upholding previous case law, held that “knowledge of a foreign language cannot, in general, be assumed”.

In relation to the case at hand, the Court held that:

- Even if that were the case, the point relates to letters or symbols in the language spoken by the relevant consumers; and

- The letters Ø, ϕ and Ф are not used in French, which is spoken by the relevant public. Those letters therefore belong to foreign languages.

As a result of these points, the Court held that the Applicant’s assertions were irrelevant for the purpose of assessing the perception of visual similarities between signs which, like the signs at issue, represent letters that do not exist in the relevant consumers’ language.

Phonetic comparison

The BoA found that phonetic comparison was not possible because neither sign has meaning for the majority of the relevant public and therefore would not be verbalised.

The Applicant argued that: “Consumers, even without understanding those languages, know that, first, the mark applied for has a meaning in the ‘Scandinavian languages’, represents a letter in the Danish alphabet and means ‘island’ in that language and, secondly, the Earlier Mark represents a letter in the Greek and Bulgarian alphabets.”

Rejecting the Applicant’s arguments in this regard, the Court again relied on the fact that knowledge of foreign languages cannot be assumed and held, inter alia, that:

- It is difficult to establish with certainty how the average consumer will pronounce a word from a foreign language in their own language;

- It is far from certain that the word will be recognised as being foreign;

- Even when the word is recognised as being foreign, it may not be pronounced in the same manner as in the original language; and

- In the assessment of the likelihood of confusion, it will still be necessary to establish that a majority of the relevant public has the ability to pronounce the word in question correctly.

Conceptual comparison

The BoA found that a conceptual comparison was not possible. The Applicant contested this, arguing that:

- The relevant public will recognise the signs at issue as being two letters from different foreign languages; and

- The letter Ø, represented by the Contested Mark, has other meanings understood by consumers across the EU (such as the number zero).

The Court upheld the BoA’s decision and reasoning in finding that for the majority of the French-speaking public, which does not understand Bulgarian, Danish or Greek, the earlier sign has no meaning, from which it concluded that no conceptual comparison of the signs at issue is possible.

Global assessment

The Applicant accepted that the distinctive character of the Earlier Mark is low and that the visual aspect of the signs at issue in the overall impression created by them plays a greater role than their phonetic and conceptual aspects.

However, it maintained that on a global assessment, no likelihood of confusion arose. Unsurprisingly, having failed in all the individual elements above, this argument also found no favour.

It’s hard not to wonder whether the outcome of this decision was inevitable once the parties agreed that the relevant public for assessing the marks was “the French-speaking public with no command of Danish, Bulgarian or Greek”.

Where a figurative mark represents a letter of an alphabet, careful consideration needs to be given by a mark owner or applicant as to how that mark will be considered or understood by consumers who have no familiarity with the language to whose alphabet the mark belongs.

Key points

- Defining the relevant public can be crucially important if the application is for a mark that represents a letter in a particular alphabet

- Knowledge of a foreign language cannot be assumed

- If the relevant public does not speak the foreign language of the applied-for letter/alphabet, then a phonetic and conceptual comparison will not be possible

Brian Conroy, a Trade Mark Attorney at Keltie, co-authored this article.

Read the full issue