How brands are keeping up with consumers

We are used to seeing logos and words used a trade marks, but there is a world of other devices being used by brands in today's connected world to catch our attention.

Traditional trade marks, such as words or logos can be seen everywhere, from the supermarket, to shopping malls and our skyline.

However, in today’s world of smartphones, influencers and 24/7 connection, brands are increasingly using non-traditional trade marks to catch our attention and build consumer loyalty.

Non-traditional marks include:

- 3D shapes

- colours

- sounds

- movements

- holograms

- smells

- taste

- textures

Engaging all the senses allows brands to build a sensory marketing experience and to the extent these become synonymous with a brand they want to ensure they have trade mark protection.

But how easy is it to obtain protection for non-traditional trade marks? While it has always been possible to register non-traditional trade marks, historically it has been tricky.

Trade marks confer a perpetual monopoly so allowing one business to register a particular colour or shape, and prevent anyone else from using it in various ways has to be scrutinised carefully.

Recent changes in the law should make it easier to register such marks but it remains to be seen how robust they will be if challenged by competitors.

How can you obtain strong protection for non-traditional trade marks?

You need good evidence of use of the non-traditional mark, preferably on its own without logos and word marks. Many are not inherently distinctive, so you will also need good evidence that it has acquired distinctiveness such that consumers really do equate the mark with the goods or services.

Lastly the representation of the mark must be clear and precise – defining the exact scope of protection you are claiming.

Shapes

Shape marks are often used to capture unusual packaging shapes for products, provided that the mark is distinctive enough to identify the brand based on the shape alone.

The shape cannot be a result of the product’s nature, add substantial value to it nor obtain a technical result.

Your kitchen may contain a number of icon shape marks. The classic coca cola bottle, the toblerone bar, the Heinz ketchup bottle, your marmite jar, Jif lemon and the polo mint all have shape mark protection. So do the Le Cruset casserole dishes, your Addidas trainers and Black & Decker power tools.

However, shape marks are not limited to goods found in the home – the iconic red phone box, pillar post box, black taxi cabs, mini cooper cars and your Starbucks take away cup all have shape trade mark protection.

In fact, BP, Esso and Apple have successfully registered marks that capture their unique retail formats.

However, some shape marks have not been successfully maintained. Recently Nestle’s EU TM shape mark for the four finger Kit Kat was invalidated. As the shape mark was inherently non-distinctive, Nestle needed to provide evidence that it had acquired distinctiveness in every EU Member State, which it had failed to do.

Colours

Colours are not distinctive per se but when a colour, or combination of colours, are used consistently and consumers identify that colour with the brand, then it may be possible to register it as a trade mark. Colours or colour combinations must be described by reference to a colour classification system like Pantone and be a clear and self-contained sign in the context it is used.

Successful applicants include Kraft for its Milka chocolate lilac, 3M for the post-it notes’ canary yellow, Tiffany & Company for its icon light turquoise blue and Heinz with its turquoise blue from its baked beans tins.

Colour combinations include Black & Decker’s distinctive yellow and black, The All England Lawn Tennis Club’s Wimbledon purple and green and Red Bull’s blue and silver.

However, clearly describing the mark can cause issues. Cadbury’s attempt to trade mark the “Dairy Milk” purple was unsuccessful, not because the colour wasn’t distinctive of Cadbury’s chocolate – it was – but because the wording used:

“The colour purple (Pantone 2685C), …, applied to the whole visible surface, or being the predominant colour applied to the whole visible surface, of the packaging of the goods”, wasn’t precise enough.

The “predominant” wording opened the door to a multitude of different permutations and visual forms that were not part of the application. These represented an unknown number of signs. This meant it was not a certain or precise description and furthermore, unfair to competitors.

Smells and tastes

As part of the sensory experience brands want to create, smell can be very important.

However, this is one area where it is extremely difficult to obtain a registration. Smell is a subjective sense and currently there is no way of representing “a smell” that is clear and precise.

One of the earliest smell marks registered (EUTM No. 428870 now expired) was “The smell of fresh cut grass applied to the product”, which in this case was tennis balls. Goodyear Dunlop had a registration (UK TM No. 2001416 now expired) for “a floral fragrance/smell reminiscent of roses applied to tyres”. And Unicorn Products Limited has a registration (UK TM No. 2000234) for a mark comprising “the strong smell of bitter beer applied to flights for darts”.

Whether these smell marks would survive a challenge to validity is questionable. Registration today remains very difficult because of the lack of technology to store and reproduce them for a register.

Many smells contain complex combinations of underlying fragrances but even if the smell is from a single compound, providing a chemical formula isn’t acceptable.

Furthermore, brand owners can’t deposit scent samples with the registry. Partly this is because of difficulties created for anyone searching for similar marks but also as trade marks can be perpetual, a chemical or organic product deposited on application could degrade over time.

For similar reasons, taste marks have not, to date been possible.

Sounds and movements

Like other non-traditional marks, sound and movement trade marks often lack distinctive character. Businesses seeking to register such marks need to demonstrate that they have acquired distinctiveness such that consumers identify the brand with the sound or movement trade mark.

This can be a high hurdle as it can be difficult to demonstrate that the consumer understands the sound or movement to be indicative of a particular brand. The second issue is providing a precise and clear description.

For a jingle or musical sound, then musical notation can be used. McDonald’s has a registration for its “I’m lovin’ it” jingle for restaurant services.

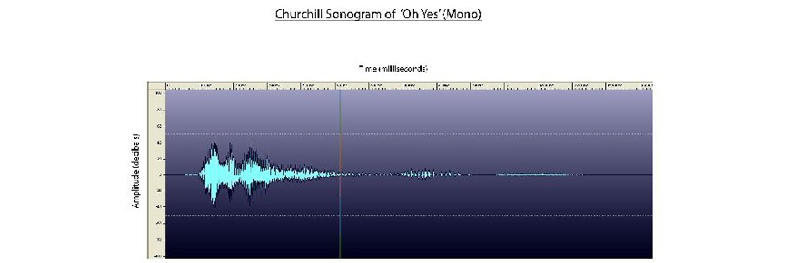

Whereas, UK Insurance Limited’s “Oh Yes” catchphrase said by Churchill the dog, is registered as a sonogram.

Historically, the bigger issue was non-musical sounds, particularly onomatopoeic sounds. While Akzo Nobel Coatings International B.V. has a registration for: “The mark consists of the sound of a dog barking” for paints, varnishes, lacquers and preservatives… (UK TM No. 2007456) this isn’t usually considered clear and precise enough.

Without a sound file (now possible) one could speculate what type of dog was barking. Those familiar with the Dulux brand might link it with the Old English Sheepdog Dulux Dog but identifying a bark based on mere description is difficult.

However, since October 2017, it has been possible to submit small MP3 (sounds) and MP4 (motion, multimedia and holograms) files. Now the MGM’s lion’s roar or the HBO’s 5 second TV static with celestial choir hum could be uploaded to the register for listening and we might be able to distinguish between the Dulux Dog and the Andrex Puppy.

Previously trade marks that contained movement had to be shown frame-by-frame like a stop-motion animation such as Nokia’s clasping hands, the Bad Robot’s animation sequence or the familiar Microsoft start-up sequence.

All of these movement marks could now be uploaded as a short film or animation. This is likely to be an area of significant expansion in the coming years as short video clips and animations are increasingly being used online and through channels such as YouTube, Instagram and Facebook. Not only are videos and animations potential trade marks but there the possibility that filters created and applied to get a certain “look” might become distinctive and therefore capable of being registered.

The expansion of online content and increasingly sophisticated marketing campaigns that engage all senses is a potential boon for non-traditional trade marks. Consumers are becoming increasingly educated to pick up on brand cues beyond words and logos. It remains to be seen if trade mark law manages to keep up.