It’s a lock

Abdulmalik Lawal reports on a decision in favour of Huawei which took a strict stance on similarity

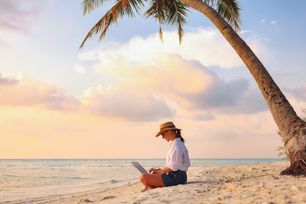

Chanel has lost an appeal against its denied opposition of a Huawei figurative mark. The Huawei mark consisted of two interlocking letters positioned in an inverted mirror image, with curved portions interlaced and intersecting with each other to produce a central ellipse resulting from the intersection of the curves.

The difference in orientation of the elements of the marks played a key role in the decision.

Initial timeline

On 26th September 2016, Huawei Technologies Co. Ltd (Huawei) filed an EU trade mark application for its figurative mark. The trade mark application covered a number of goods in class 9, including “computer software applications, downloadable; earphones and headphones; cases for smartphones; [and] protective films adapted for mobile phone screens”.

On 28th December 2017, Chanel filed a notice of opposition based on two grounds. The first was Article 8(1)(b) EUTMR, relying on Chanel’s earlier French

registration FR 3977077 (FR’077), which covered inter alia goods in class 9, including computer software, headphones, and protective films for mobile phone screens. The second was Article 8(5) EUTMR, relying on Chanel’s earlier French registration FR 1334490 (FR’490), which covered goods in classes 3, 14, 18 and 25.

On 19th March 2019, the Opposition Division (OD) rejected the opposition in its entirety. Chanel subsequently filed an appeal against the decision of the OD, which it lost. It then appealed its failure before the Board of Appeal (BoA) to the General Court (GC).

Appeal decision

The Fourth BoA dismissed the appeal on the basis that the marks in question were not similar.

In relation to Article 8(1)(b), the BoA was of the view that the Huawei mark consisted of two interlocking U-shaped elements in a vertical position surrounded by the basic geometric shape of a circle, while Chanel’s FR’077 mark consisted of two bold, black, interrupted circles, placed mirror-like and overlapping in a horizontal position.

Visually, the BoA thought the marks produced a very different overall impression. It concluded that the mere fact that each of the marks was composed of two connected elements did not make them similar.

The BoA concluded that, overall, the marks at issue were dissimilar for the purposes of applying Article 8(1)(b).

In relation to Article 8(5), the BoA observed that from a visual point of view the Huawei mark and Chanel’s FR’490 mark had a different structure and were composed of different elements. It also observed that the marks were also not similar from a conceptual point of view.

Since the marks were dissimilar, the BoA concluded that the first of the cumulative conditions required to satisfy protection under Article 8(5) (the marks at issue must be identical or similar) had not been satisfied, and thus the opposition under said provision had to be rejected on that ground alone. The BoA concluded that it was not necessary to examine the other conditions for the application of the provision.

GC decision

Chanel relied on two pleas in law when asserting that the BoA made an error of assessment when it rejected the opposition, in so far as it was based on Article 8(5) and on Article 8(1)(b).

In its Article 8(5) plea, Chanel argued that the Huawei mark and the FR’490 mark were similar overall to an average degree when they are viewed in the orientation in which they are applied for and to an average to high degree when the Huawei mark is rotated by 90 degrees.

It argued that the BoA ruled out as a matter of principle any possibility of taking into account the mark applied for in an orientation other than that in which it had been filed on the incorrect ground that trade marks should always be compared as applied for and registered.

Chanel claimed that it is permissible, by contrast, to take account of the different orientation of one of the signs if it corresponds to the perception which, irrespective of the intentions of its proprietor, the public may have of it when the mark is affixed to goods on the market.

The GC pointed out that when assessing whether marks are identical or similar, they must be compared in the form in which they are protected – that is to say, as they were registered or as they appear in the application for registration. It concluded that the case law relied on by Chanel could not call such a finding into question.

On comparison of the marks, the GC noted that the marks at issue shared certain characteristics but that there were visual differences which, when assessed globally, result in the marks being visually different.

Conceptually, it considered the marks to be different because the Chanel mark included the initials of its founder, while in the Huawei mark it was the stylised letter “H” or two interlaced “U”s that would be perceived as a part of the mark.

In its Article 8(1)(b) plea, Chanel put forward similar arguments in relation to the similarity between the Huawei mark and the FR’077 mark. The GC assessed the marks in question and noted that the circle present exclusively in the Huawei mark gave it a specific arrangement and proportions that are not present in the FR’490 mark. It concluded that while the marks at issue share characteristics, the absence of a circle in the FR’490 mark and the consequent arrangement rules out any visual similarity.

The GC found that the BoA had been correct in its finding that the marks at issue were dissimilar overall and that the opposition should be rejected. I wonder if Under Amour, Inc. would have had a more favourable outcome if it had opposed the Huawei mark on the basis of its figurative mark.

Key points

- It is necessary to compare marks in the form in which they are registered

- A strict comparison of the elements may result when assessing purely figurative marks